2.3. Lecture 2: Complexity science¶

Before this class you should:

Read Think Complexity:

Preface; and

Chapter 1: Complexity Science

Sign up (via Office Shets - see link on CourseLink announcement) to be the primary contributor to one lecture in the course notes or an in-class debater.

Before next class you should:

Read Think Python:

Preface;

Chapter 1: The way of the program;

Chapter 2: Variables, expressions and statements; and

Chapter 3: Functions

Note taker: Ethan Lima

2.3.1. Overview¶

Today’s class was an introduction to Complexity Science. During the lecture, we:

Introduced ourselves to others in the class via breakout groups

Created a “Web of Life” to describe a problem with different variables that contribute to it and how they relate to each other

Learned the difference between a convergent and a divergent problem

Discussed the barriers of learning (delays, feedback loops and disconnection between consequences and actions)

Learned about complexity science and the implications of it

Modelled changes and biases using the “Parable Polygons” model

Discussed classical and complexity models of science, engineering, and thinking

2.3.2. Breakout Groups¶

During class, we made breakout groups where we introduced ourselves and discussed who has the most and least previous Python experience. We then choose a question to ask about the course and nominated someone to ask them.

One of the main questions that was asked was What is the difference between the in-class debater role and the reflections and participation in debates?. The answer provided by the prof was:

In-Class Debaters: assigned a topic and a side to take during the debate

Reflections and Participation in Debates: only take place between March 10 to March 31 and debate based on the Situational Awareness text content for the week

2.3.3. Web of Life & Different Types of Problems¶

During the class, we made a “Web of Life” diagram to showcase different problems (variables) and how they relate to each other. The goal of the web is to help visualize the complexity of a problem by identifying the connections between each variable. The steps to make a “Web of Life” diagram are provided below.

Steps to make a “Web of Life”:

Share interrelationships that exist within your environment by referencing a specific problem, issue, or behavior

Identify key variables and assign individuals to represent each variable

Designate “lead” and have them start the whiteboard, position each member around them

Have one person suggest how their variable compares to someone else’s and explain the connection

The recipient explains how their variable relates to others in the web and passes it on to someone else to continue the cycle

As the cycle continues, more connections to variables are made resulting in a web of connections over time

Example: a problem could be “being bad at video games”

Variables: no time, school, too tired to play, bad aim, learning curves, expensive, bad teammates

Possible connection: one might have no time to play video games because they are focusing on schoolwork, and since they cannot train often, this may result in having bad aim

Convergent Problem

A convergent problem is an issue in which there is a universally agreed-upon or most efficient solution. An example of this is using a GPS to avoid traffic when getting to work, which is the optimal way to make it as soon as possible.

Divergent Problem

A divergent problem is an issue in which there are many valid solutions and no objective “best” one. An example of this is that there is no “best” way to educate a child, as many strategies work.

“The systems thinker’s forte is recognizing interdependence” - Barry Richmond

The job of a system thinker is to identify links between solutions and recognize that as the scale of a problem changes, so does the design of the solution

2.3.4. Barriers to Learning¶

It can be difficult to learn when any of these factors are present:

Significant delays between actions and consequences of the action

Multiple feedback loops

Non-linearities between actions and consequences

Discussion

Where are the significant delays in the web?

Students balancing between studying and playing games

The job market needing higher-skilled workers means more time to train

Where are the multiple feedback loops?

Increasing funding means more taxes, making it more expensive to run hospitals

Students spending more time in school and less on gaming

Bad at aiming in video games: no time to train because of school

Expenses: more money on school, not enough for gaming

Where might there be a disconnect between consequences and actions?

The disconnect between consequences and actions arises when based on the magnitude of changes made to the system. Therefore, if a small change is made to a system, the consequences and effect on the system will also be small. On the other hand, if big changes are made, the consequences and effect on the overall system will be greater.

An example of this is funding for a hospital. If the funding is decreased a little, then hospitals may have slightly tighter budgets. If the funding is decreased dramatically, then they might not be able to afford the equipment to take care of some of their patients.

Another example is a student balancing their time between schoolwork, sleep, and playing video games. If a student stays up a little later than usual playing games, they might wake up later and potentially miss a class. However, if a student is staying up significantly later, they might miss classes and time that could have been used to complete assignments and homework.

Both of these examples demonstrate how feedback loops work as well. For example, if a student stays up late consistently, they may fall behind in course content and potentially miss assignment or lab due dates.

2.3.5. Complexity Science¶

Complexity science is used to describe how variables in a problem change over time and how they can be modeled given the parameters of the problem. The general idea is that as the scale of a problem gets larger, certain models may no longer be sufficient enough to describe the problem accurately. Complexity science changes what we mean by “science”, since the solutions and models made may not be entirely accurate or only work given certain restrictions.

An example of this is traffic flow. The flow of traffic on a summer day can be modeled easily. However, if we were to consider traffic flow during the winter, there would be more factors involved, such as road closures and car accidents which can all affect the flow of traffic.

Another example is predicting the climate versus the weather on a given day. The general climate can be predicted based on the weather from previous years (if it was cold in January last year, it will be cold in January this year). On the other hand, the weather in Ontario can change drastically depending on various factors such as the weather in other provinces.

Complexity Science With Scalability

As the scale of a problem increases, previous solutions may not be valid representations of the problem anymore. For example, Newton’s laws of gravity can be used when describing how gravity affects humans on Earth. However, if these laws were to be applied galactically to describe how objects move across space, new models would need to be made to represent this.

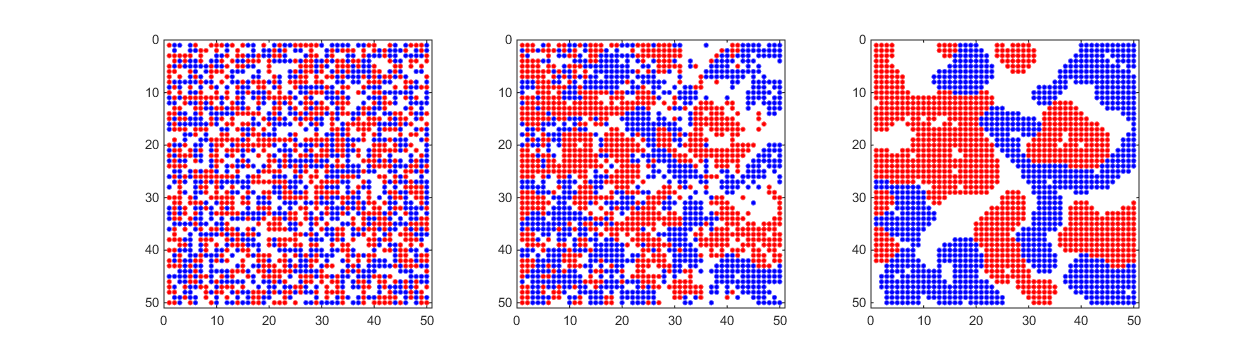

Parable Polygons

Small bias, can lead to large bias and therefore consequences

Schelling’s model of Segregation:

From: GitHub - Source: Rafal Kowalski

Factors that affect segregation:

Direction of movement

If there are more than just 2 shapes (variables involved in the problem)

Expenses required to move

Axes of Scientific Models

Classical Science:

Equation-based

Analysis

Continuous (ex. continuous math like calculus)

Linear

Deterministic (fixed variable attributes, ex. gravity is 9.81 m/s^2)

Abstract (simplifications or assumptions are necessary, ex. frictionless systems)

Only a few variables are taken into account

Homogeneous (identical variables and interactions)

Mainly used for predictive simulations

Complexity Science:

Simulation-based

Computation

Discrete (ex. discrete math like graphs)

Non-linear

Stochastic (random variables)

Detailed (realistic systems with less assumptions, ex. friction is taken into account)

Many (takes into account a large number of variables, with various interactions for each)

Heterogeneous (various types of variables and interactions)

Mainly used for explaining how systems work (explanatory)

Both models have their own purposes depending on the size and complexity of the problem. For example, classical science is predictive and should be used in cases with a low number of variables and interactions. Complexity science, on the other hand, is explanatory and can be used to solve problems with multiple variables and interactions.

Classical Science Purposes:

Predictive

Realism

Reductionism

Complexity Science Purposes:

Explanatory

Instrumentalism

Holism

Two Body Problem:

Classical models can be used to solve these problems efficiently

Three Body Problem:

Adding another variable into the problem means there are more possible solutions (some of which may be more optimal than others)

Solutions provided using classical science may not be optimal/feasible, therefore classical model begins to breakdown

“All models are wrong, but some are useful” - George Box

Some models may be useful for modelling systems and are sometimes near optimal, but are ultimately not fully correct

2.3.6. Complexity Engineering & Thinking¶

Classical Engineering:

Centralized (easier to analyze, but not very robust)

Isolating connections from one variable to many others (one-to-many)

Top-down

Analysis

Design

Used for analyzing/visualizing systems

Complexity Engineering:

Decentralized (harder to analyze, but displays the robustness of a system)

Interaction/connections between multiple variables (many-to-many)

Bottom-up

Computation

Search

Used for computing results from system interactions (searching for solutions)

“Engineering is a search for solutions in a landscape of possible designs”

Example of a Machine Learning System:

“Machine Learning Cookie” - Made a cookie recipe and got feedback on it

Adapted the recipe to feedback to create the optimal cookie recipe that satisfies everyone

Classical Thinking:

Aristotelian logic (variables have fixed behavior, answer relies on mathematical proofs and is either true or false)

Objective

Physical law → theory (a solution is proven to be true or false)

Determinism (“caused by past events”)

Complexity Thinking:

Bayesian logic (variable behavior varies, update probabilities as more knowledge is gathered about the problem)

Subjective

Model (subjective based on simplifications made when designing the model)

Indeterminism (“model real events”)